The time of things Rosana Paulino

In Racismo e Sexismo na Cultura Brasileira [Racism and Sexism in Brazilian Culture], Lélia Gonzalez understands the Brazilian cultural neurosis as the rejection of the pluri-racial and pluri-cultural make up of Brazil, which is materialized in denial. Gonzalez explains how this idea promotes the erasure, the repression and the suppression of cultures via their subalternization. This includes the notion that there is a Brazilian culture that belongs to a European legacy and has allowed the influence of certain Indigenous and Black-African cultural elements into its formation. Such understanding draws on a form of hierarchization that signals and determines the superiority of the European element in relation to the savage and grotesque place of Otherness. This hierarchization has a direct influence on the discourse that defines non-white religions, customs, languages, modes of social organization and ways of life as primitive and without history. From this perspective, there is also a second pair of opposites that coexist: that of consciousness and memory. It is in consciousness that we find history and the hegemonic discourse that underpins the project of a Brazilian nation and that, whilst maintaining the Black population firmly in the condition of alterity, defines them via infantilization and stereotypes. In turn, it is memory that recovers the unwritten history. Memory is the leg sweep, the takedown move.

Lélia Gonzalez also describes how the notions and images of the Black mulata, the Black domestic worker and the Black mother, which recurrently inhabit the version of history engendered by institutions, are the same notions that define the place of Black women in the formation of Brazilian culture, through different forms of both rejecting and incorporating their role. Nonetheless, there is ginga(1) underneath each layer of consciousness to be excavated. By rejecting the subaltern place of oblivion, tragedy and colonial binarism, Gonzalez highlights that it is precisely the Black woman who ultimately delivers the leg sweep against the dominating race: she is the crucial link in the dissemination of pretoguês(2), the language that, even without noticing, the dominant race speaks.

Memory – that which escapes the control of the ideal of white-centric Brazil – witnesses the permanence of time: the past-present that emerges from the enunciation of the unspeakable; that we can see in what is meant to be hidden; that reveals what should be concealed; but nonetheless continues to exist, both in our spoken language and in the images we produce.

The work of Rosana Paulino destabilizes prevailing representational models through the use of disturbing images. It enunciates and emphasizes what is most obstinately omitted. In the video Das Avós [Of Grandmothers], Western Jewish-Christian linear time is suspended – the same suspension that appears in other works by Paulino – when images of Black women belonging to an uncomfortable past, seen in historically produced photos used as cartes de visite and illustrations of slavery, are found and carefully brought to the foreground, revived, stroked and sewn together, so they are never forgotten or trapped forever in the discourse that has smothered their subjectivities.

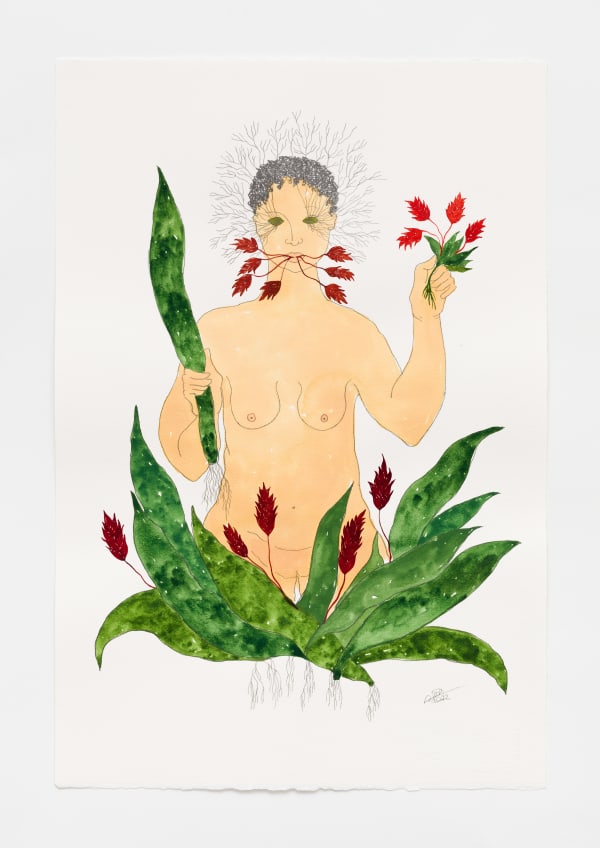

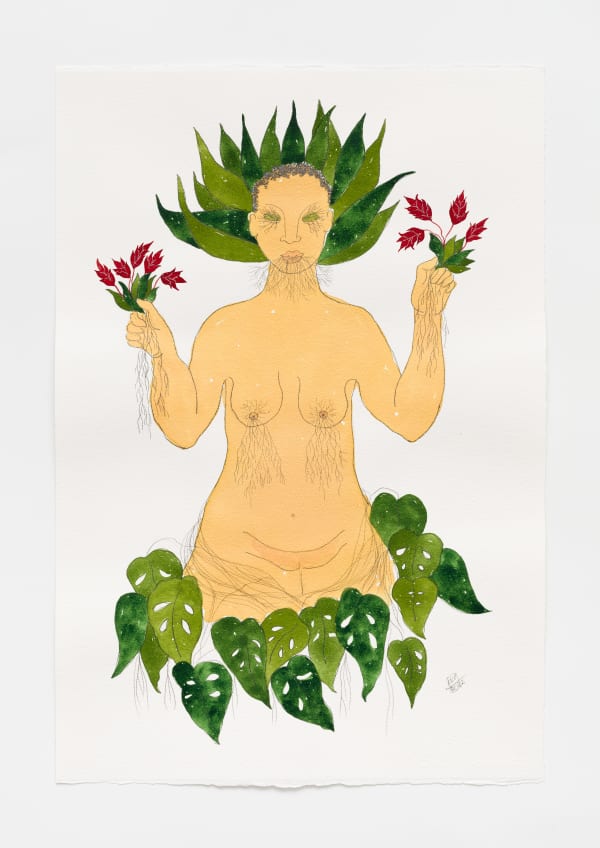

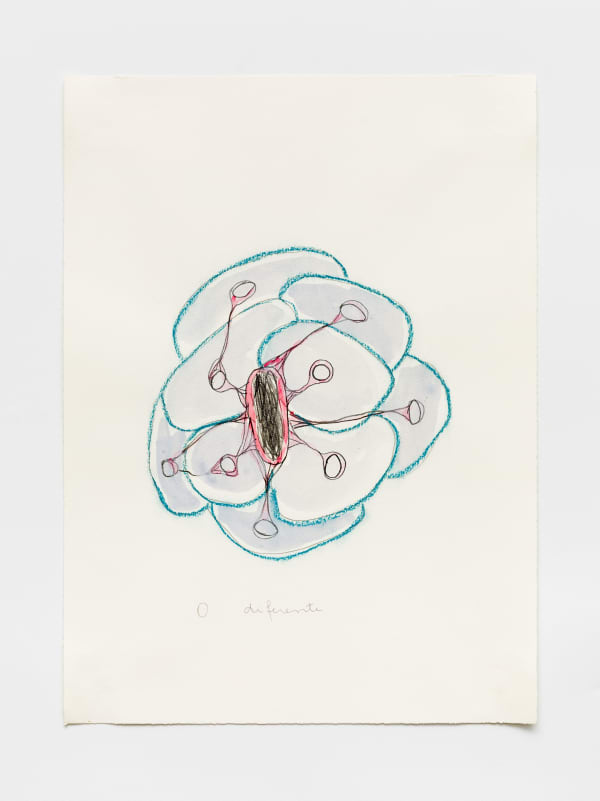

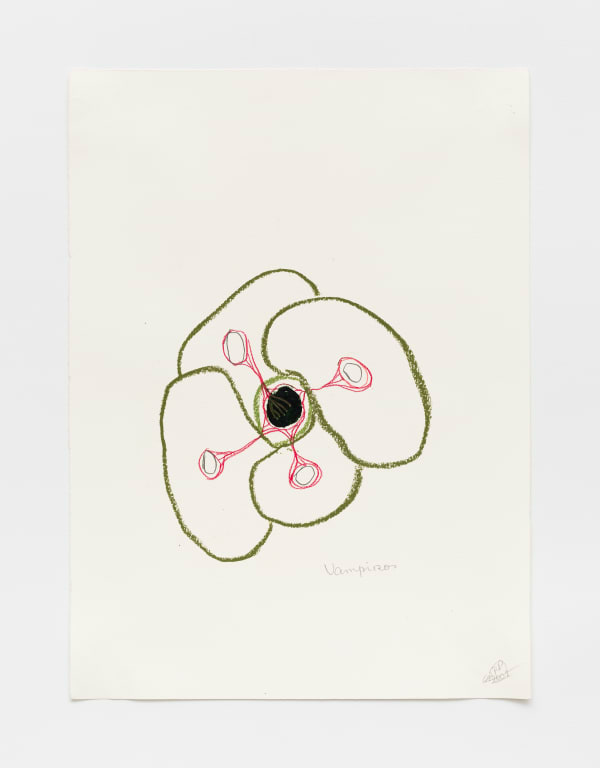

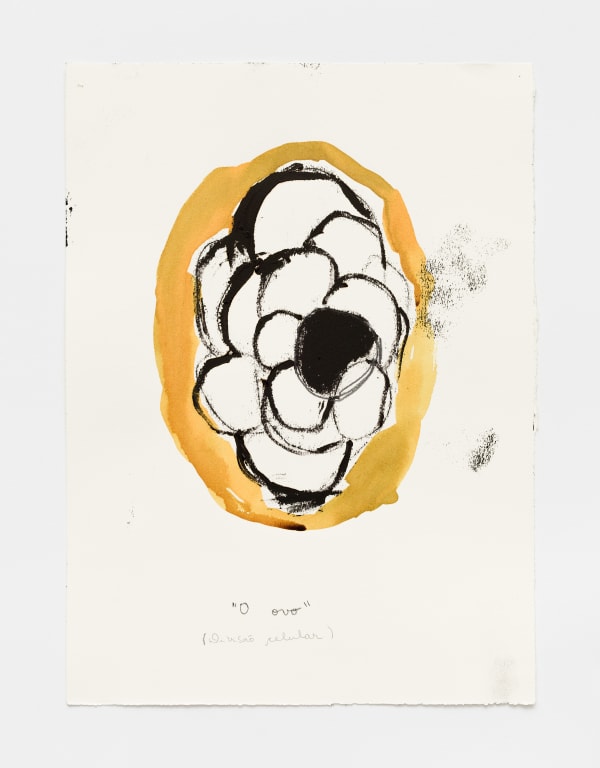

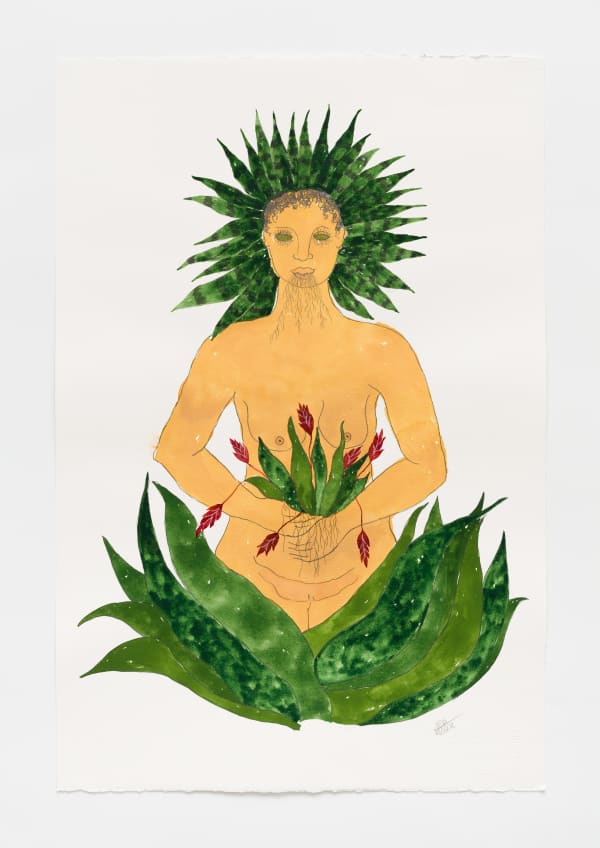

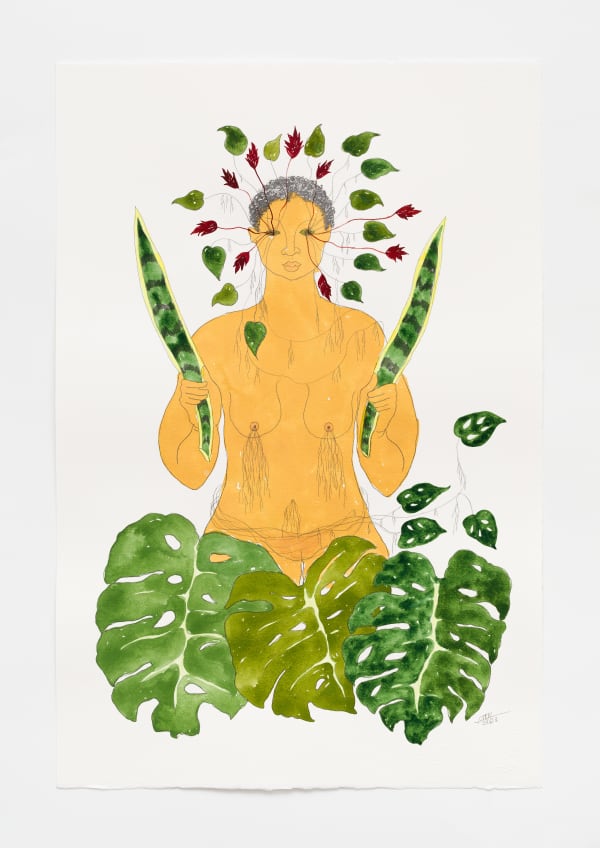

The Black female body collects layers and layers of oppression – of race, gender and class. But it is this racialized female body that remains, in its utmost complexity, unrepresentable by white-centric lenses. Despite the lack of language and vocabulary in the so-called Western arts to deal with these existences, in the series Senhora das Plantas [Lady of the Plants] (2022), Rosana Paulino makes use of plants that are significant in Afro-Brazilian cultures, such as the dracaena trisfasciata (the sword of iansã), the Swiss cheese plant, the dragon-tail plant and the bromelia, to create, through a symbolic nature, a regime of visibility that allows the complexity of Black female subjectivity in the diaspora and its archetypes to be perceived.

By turning her attention to the diaspora, the artist produces works that draw on the uncomfortable, offering a mirror to those who walk around her pieces, so they can also feel part of a delicately interwoven network: Europe as a whole benefited from slave traffic. There is no innocence to be preserved.

Images, nomenclatures and frameworks of classification are also far from innocent. Rosana Paulino accesses the archive that we call the history of white-Brazilian art, examining the inventory that has, for a long time, legitimated the project of Brazil as a tropical paradise, a place of exotic plants, animals and peoples, confronting the ideal of tropicality and Brazilian-ness perpetuated by this perspective. Her paintings, drawings and collages hold the signs of things that history has opted to obscure. It indicates the time of things in the state of Maafa, and the permanence of time in our structures.

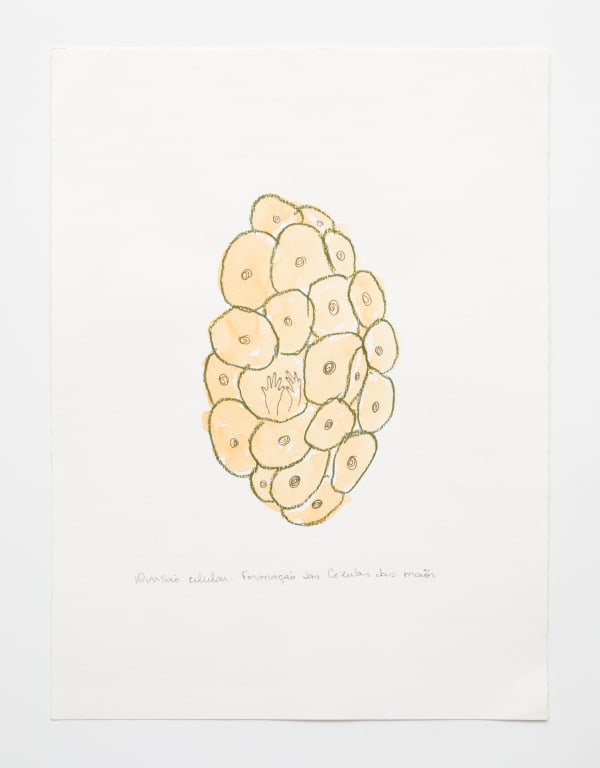

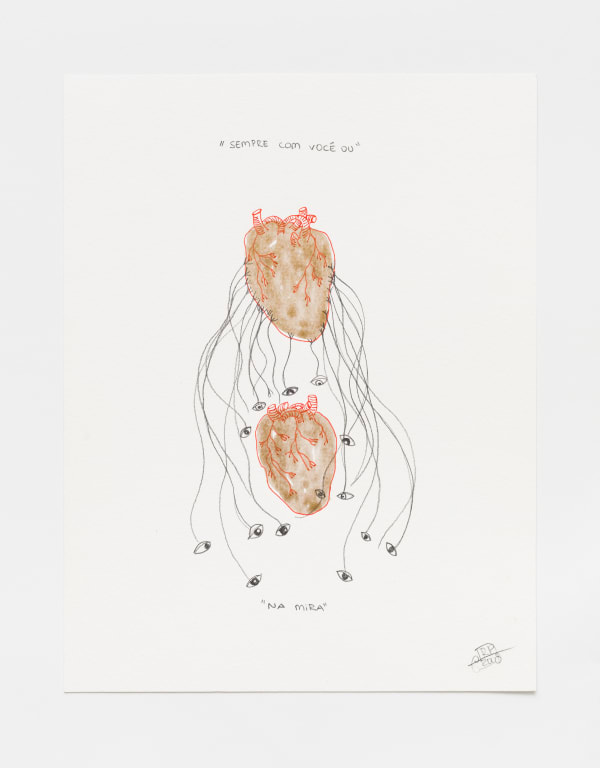

These rigid structures, impotent in their power, inertly watch the blossoming of open-ness, of defiance, and the eruption of things that matter. The leg sweep, the element of surprise, the ginga. Small cocoons seem to hold a prohibited subjectivity, interspersed with the yearnings, desires and visions of a Black body that cunningly avoids the Brazilian cultural neurosis, playing with time and projecting life.

– Lorraine Mendes

GONZALEZ, Lélia. Primavera para as rosas negras: Lélia Gonzalez em primeira pessoa. São Paulo: Diáspora Africana, 2018.

[1] Ginga is the fundamental swaying movement of capoeira, characterized by a continuous, flowing movement, allowing for defence or unpredictable attack.

[2] According to Lélia Gonzalez, the pretoguês is a Bantu presence in the language. It is a way of marking the African component in the language spoken in Brazil, not as a variation, but as what, according to the author, truly constitutes it.

-

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino -

Rosana Paulino

Rosana Paulino