Ode to Twisted Gods Pol Taburet

Ô paysage de diamant violenté de mains d’acide […] » 1

Anthony Phelps, Motifs pour le temps saisonnier, 1976

Culture is not monolithic; it is a muddy silt that carries with it the stories of great ecstasy of our ancestors as well as their most tragic ones, one which we try and probe as best we can. It is an infinite archipelago whose islands undergo a motion contrary to the drift of continents, inevitably drawing closer to collide, creating breaches and sculpting mountains. Pol Taburet knows this, because he belongs to a generation for whom the world is almost entirely available, collecting and accumulating scattered elements from still disjointed areas of culture to merge them into a new, inevitably hybrid experience.

One evening, while he sits on the Praia da Porto da Barra, Pol calls himself a romantic artist, hoping, under the starry and endless night, for the blessing of a William Blake or a Francisco de Goya. “Neo-Afro-Romantic”, he specifies, because to be a romantic is first and foremost to resist fixed definitions; it is to cultivate the fertile land of contradictions and boundaries, the ones that stand between the real and the imaginary, past and future, facts and myths, North and South, alienation and elevation, commercial culture and authentic culture.

Since Michaël Löwy and Robert Sayre’s retelling of its history, we know romanticism to be more than the realm of frivolous and desperate souls, withdrawn into their own tears like bourgeois in their abodes. Romanticism offers a “modern critique of modernity”, that counters reality with a “critical unreality”. Blake wondered if the hills of England, now blanketed with these “dark Satanic Mills”, once used to be home to a “Countenance Divine”; an old Haitian proverb answers by saying that “behind the hills are more hills”: that that there is more to what we see.

The hill of Bahia, a mass sparkling in the faint twilight, becomes for Pol a motif that hinders the very fantasies it invokes. Using the form of advertising billboards, he seeks to counter what he calls these “polluting and seductive images” with other images that are openly unrealistic and critical. They pronounce the verdict of shattered dreams, of an illusory El Dorado where the words of Aimé Césaire resonate, when he spoke of “landscapes of broken glasses” where “vampire flowers” can be found feeding on “the sugar in the word Brazil deep in the marsh”.

From São Paulo, where he is temporarily based, Pol builds his own universe according to coordinates that do not translate in the arithmetic language of Reason. He deals rather in the strange and subtle speak of tales and myths, those told on the occasions of the “black vigils” so dear to Léon-Gontran Damas and made of “that Creole salt that so resolutely resists translation”.

It is said that Creole tales often begin with “et cric, et crac”: a crack in the silent order necessary to the summoning of the gods. Pol has nuanced his usually fiery palette with muted shades, introducing the weight of silence into his discourse, a “silence filled with silence” in the words of Édouard Glissant. But these muted colors must be confronted with the figure of a supreme god; a god of gods floating in the air, with a trumpet-like nose to sound the call for the return of spirits and upset the order of the rational world. Thus Pol summons his own cohort of gods and littles genies – those encountered only in the hearts of volcanoes, like those bronze heads that seem covered with sulfur and have taken residence atop buildings, dominating the big city. There are the mythical and ritualistic figures borrowed from Guadeloupean Quimbois, Haitian Vodou, or Brazilian Candomblé. There are also those drawn from urban legends, such as Candyman, a victim of a heinous racist crime in the working-class neighborhood of Cabrini-Green in Chicago, where he was covered in honey and subjected to the stings of bees. Legend has it that he resurfaces to seek revenge when his name is uttered in front of the mirrors in these miserable blocks of flats.

A form of melancholy sets in; it is unstable, it is hybrid, it is a saudade – a word that only exists in the Portuguese-speaking world and denotes something like a prospective nostalgia: a nostalgia for the future. Paradoxically, it is in the sorrowful mind of the modern man that his greatest hopes are born: the hopes for a return of the marginalized, for a general upending of established values; those that will bring us back to what André Breton called the “ultrasensitive parts of the earth”, where it is opportune to sing an Ode to the twisted gods.

1 “O landscape of diamonds, spoilt by hands made of acid […]” [free translation]

— Guillaume Blanc-Marianne

-

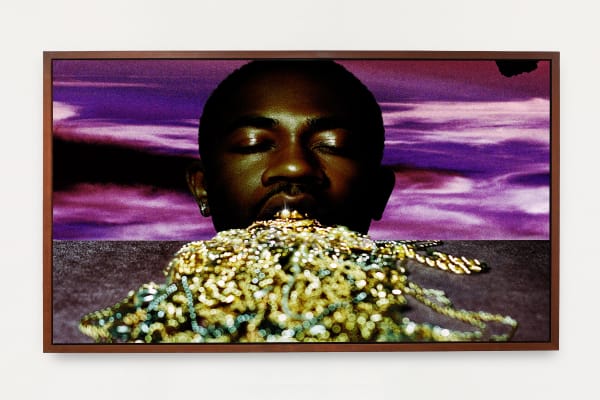

Pol Taburet, Rooted Coma, 2023

Pol Taburet, Rooted Coma, 2023 -

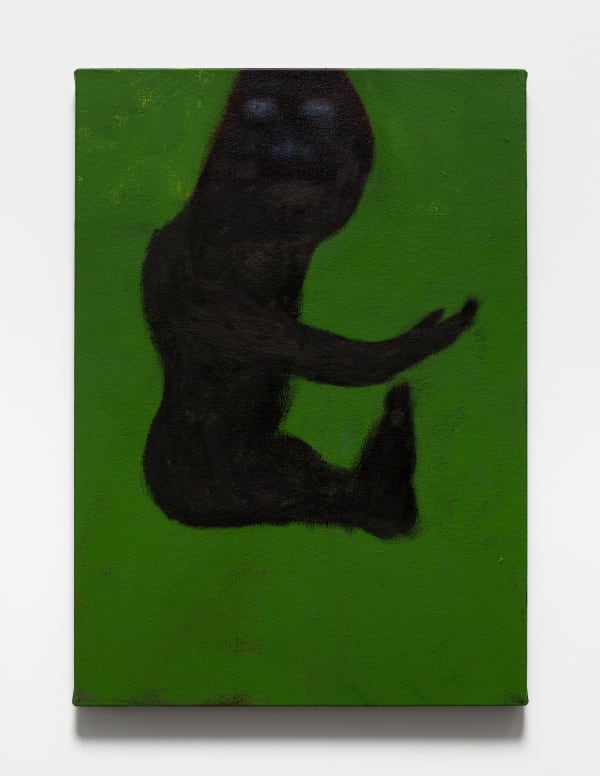

Pol Taburet, Bondage napkins, 2023

Pol Taburet, Bondage napkins, 2023 -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

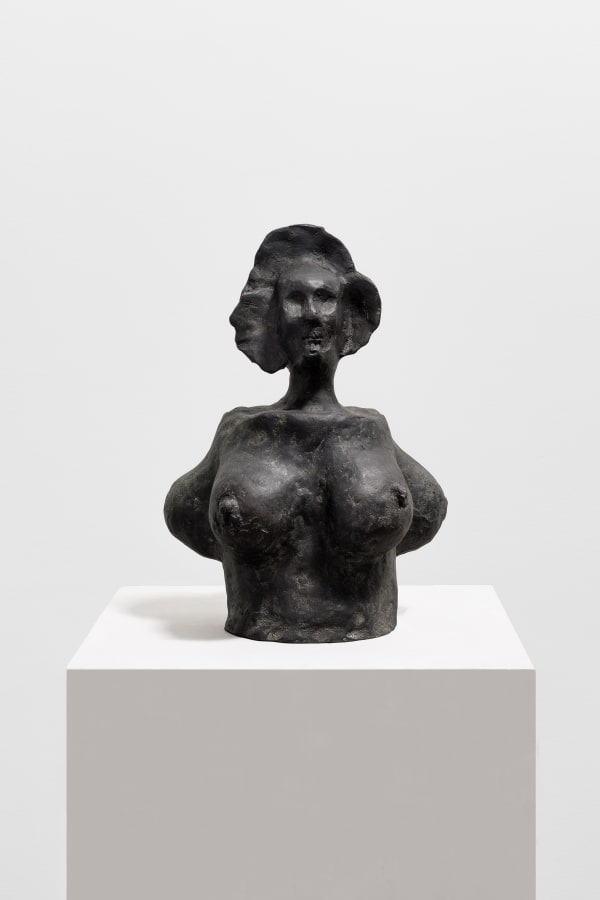

Pol Taburet, Idol, 2024

Pol Taburet, Idol, 2024 -

Pol Taburet, Silver spoon, 2024

Pol Taburet, Silver spoon, 2024 -

Pol Taburet, 4some Funeral, 2024

Pol Taburet, 4some Funeral, 2024 -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet -

Pol Taburet

Pol Taburet