Noite longa Paloma Bosquê

Click here to book your visit.

Since the sand never stops

moving or reflecting

the warmth of the sparkles, the child stayed there

all afternoon playing.

Feeling the sand penetrate her,

first between her fingers, then in her eyes,

mouth, nose, ear:

Becoming a child of sand

without realizing that the hours were passing

— Leonardo Fróe

While visiting a teahouse in Kyoto, the Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki recalls encountering a new kind of darkness, which he called “darkness seen by candlelight.”1 The atmosphere was produced by a panel that limited the room and imposed itself against the wavering light of a pair of candles. For Tanizaki, the color that bathed the room seemed to have tiny iridescent particles. “I blinked in spite of myself, as though to keep it out of my eyes,” said the writer.

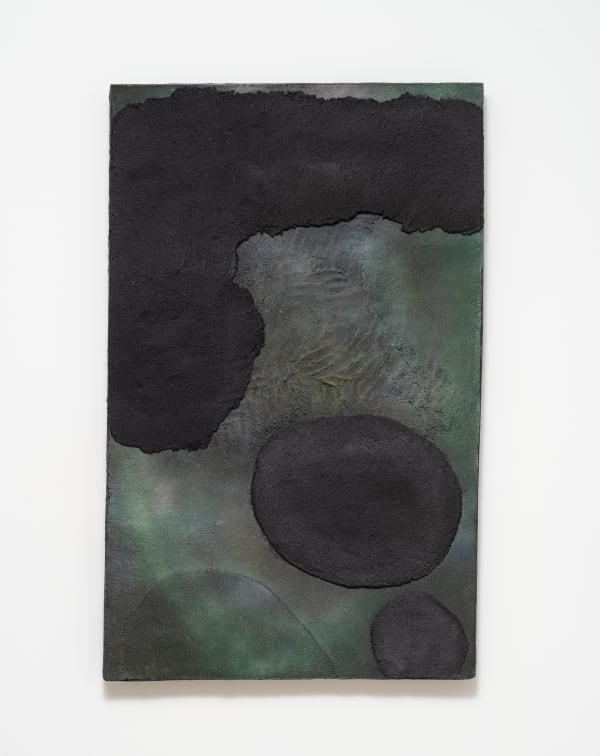

In Noite Longa, Paloma Bosquê’s new exhibition, one can sense, at certain moments, an atmosphere familiar to Tanizaki’s. The sculptures and plates that occupy Casa Iramaia make up, above all, a group of bodies whose morphology alludes to geological strata and multiform beings which, if not inhabiting the terrain of these plates, seem to share a kinship with them that is difficult to grasp – were they exiled from there? Are these plates their destination?

The plates, robust and rough, are made of layers of cotton fibers dyed black. Their gradual composition involves a game of adding and removing, removing and adding – and in this exploration of matter’s potential for accumulation, sedimentation, and erosion, Bosquê creates a kind of condensation of “deep time,” a concept developed in the 18th century by Scottish geologist James Hutton, referring to time from the point of view of slow, incessant geological transformations. In this synthesis of deep time forged through a process of artistic composition, Bosquê sees a sculptural vocabulary in geology and time. Upon reaching a rocky promontory on the east coast of Scotland where the layered soil contributed to the theory of deep time, one of Hutton’s friends wrote, “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.”

The sense of depth in Bosquê’s wall works is produced by two factors. First, the blackness that makes up these clumps is nuanced by a subtle contrast between the various layers of matter, and this same contrast gives us the impression of facing a negative mountain. Then, there are spots on these plates that are coated with resin and tinted with layers of spray paint which, when overlaid, create an iridescent effect. These resinous areas take on a glassy or watery appearance and don’t possess the average depth of a flood, but rather that of the abyssal trenches – the deepest regions of the ocean where the tectonic plates meet. Almost off-limits to humans, the deep ocean is home to prodigious life forms: Bacteria, sea sponges, anemones, and blind fish with fluorescent filaments live there, as well as all that is still unknown to us.

Iridescent colors are considered structural colors. They change depending on where you observe them and the quality of the light that falls upon them. They require not only positioning but constant repositioning in front of objects that, even when attached to a wall, resist complete fixation. On the contrary, they reveal themselves in new and often ambivalent ways as we move in front of them: In the oceanic and glossy areas of Bosquê’s plates, what was initially green takes on shades of pink, ochre, and lilac. Each color is itself and, at the same time, another.

Just as the colors evade us, the free-standing works in Noite Longe also seem to defy definitions. These strange beings, which can resemble both vestiges or somewhat monstrous physiognomies, point out unclassifiable forms of life. And they lurk, a little restless, perhaps about to flee on their absent or mangled feet. These elusive figures, whose few limbs have a meager appearance, are both singular and bipartite – raising questions about unity. One of the sculptures, for instance, is a shell-colored figure seemingly forged by two strands twisted into a kind of spiral – two limbs that at the same time are estranged and merged. To what extent can an object, or a body, be considered a whole? Is a split object capable of maintaining some kind of unity, asks the artist. Doesn’t our own body repeatedly and literally detach when we lose hair, skin, and fluids, requiring us, as subjects, to make a daily effort to reinvent our individual limits? In Short Talks, the poet Anne Carson recounts the last days of the sculptor Camille Claudel who died in an asylum: “She refused to sculpt. Although they gave her sleep stones – marble and granite and porphyry – she broke them then collected the pieces and buried these outside the walls at night.”2

Paloma Bosquê sculpts her improbable beings – perhaps unearthed from the sand – in a process that involves a certain sympoiesis (making-with), as if giving them time to demand, at a certain point, to be split in two, to lean lazily to one side or the other, to lose their limbs or even to fall apart completely. Similarly, the plates are composed through a dynamic of reciprocity between the artist’s hands and the skin of a topographic surface.

The introduction of color in Bosquê’s work, which previously focused mainly on shades of black, ecru, and variations of white, perhaps goes hand in hand with the artist’s longstanding interest in the sun – already present in In the Hot Sun of a Christmas Day (2019), One Other Night (2020) and, most recently, in Three Suns, an installation she presented in Basel in 2023. But in Paloma’s approach, the solar phenomenon – which makes it possible to see colors and life on Earth – never manifests itself in an obvious or reverential way. If the night has always been seen as the realm of mystery, today Bosquê claims that there is just as much enigma under the light as there is in the dark. The bright sun, for example, is a kind of delusion. Instead of making everything stand out, it obscures the view – heads turn downwards, hands brought to the forehead to shade one’s face – making the full day also a source of misunderstandings. And it’s only under the sun that mirages exist.

In her work, Bosquê welcomes light as an elementary exogenous factor and as a challenge – it’s possible to filter it, contest it, but also invent it and attract it with colors that reflect and confuse it – thus also confusing our points of view, in a reminder that they are never univocal. The bodies that make up Noite Longa, in their elusive and changeable texture and tonal composition, seem to ask to be revisited in the twilight, under the light of a few flames, just like in the teahouse Tanizaki encountered.

I’d like to find out if, in this dark house lit only by a fireplace, I could feel the particles of the iridescent graves invade my eyes, like fireflies or shimmering grains of sand. And if the verses of the thick plates that hold the abyss of time still cast colored shadows – auratic, shimmering – on the walls that strangely support them.

— Julia de Souza